The Singing Line

How the Overland Telegraph Line changed the history of Australia.

The Songlines

For thousands of years before Europeans came to Australia, Aboriginal people had communicated across the land with songs, stories, and legends. Their songlines radiated out across the landscape, telling tales of how the world came into being, how to navigate through it, where to find food and water, and how to behave when they encountered people from other, distant tribes.

These songs were carried by foot, slowly and inexorably across the country. They were living, breathing communication tools, constantly being amended and added to by the people who sang the songs and told the stories. And it had been that way for millennia.

The tyranny of distance

Australia is at the end of the world. Hidden in the middle of an almost endless ocean, for the country’s early settlers, the distance between Australia and the old world of Britain presented an almost insurmountable problem when it came to communication.

As Australia grew from a small cluster of convict settlements, eking out a precarious existence on the edges of the continent, to a fully-fledged nation, it needed a way for information to reach it rapidly. News, dispatches and mail from Britain took months to make the long, perilous journey to and from Australia.

The new technology known at the telegraph, which enabled rapid communication between different parts of the world, was rapidly expanding its network of copper wires and undersea cables across the globe. It was the answer to Australia’s communication problem.

Mr Stuart’s Track

There was fierce competition between Australia's colonial states about who would be the first to construct a telegraph line that would connect the country with the rest of the world.

The Victorian Government had organised the Burke and Wills expedition to cross the continent to the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1860. But although Burke and Wills did succeed in crossing Australia, the expedition expedition ended in disaster, with both men dying alone in the bush.

Meanwhile, the South Australian government had organised an expedition led by the Scottish explorer John McDouall Stuart. After six attempts, Stuart succeeded in the crossing the continent from north to south. On the 24th of July 1862, he reached the northern coast of Australia at a place that he named Chambers Bay.

At around about the same time, the Northern Territory was transferred into the control of South Australia. The aim of this was to secure land for an international telegraph connection running from Adelaide to Darwin.

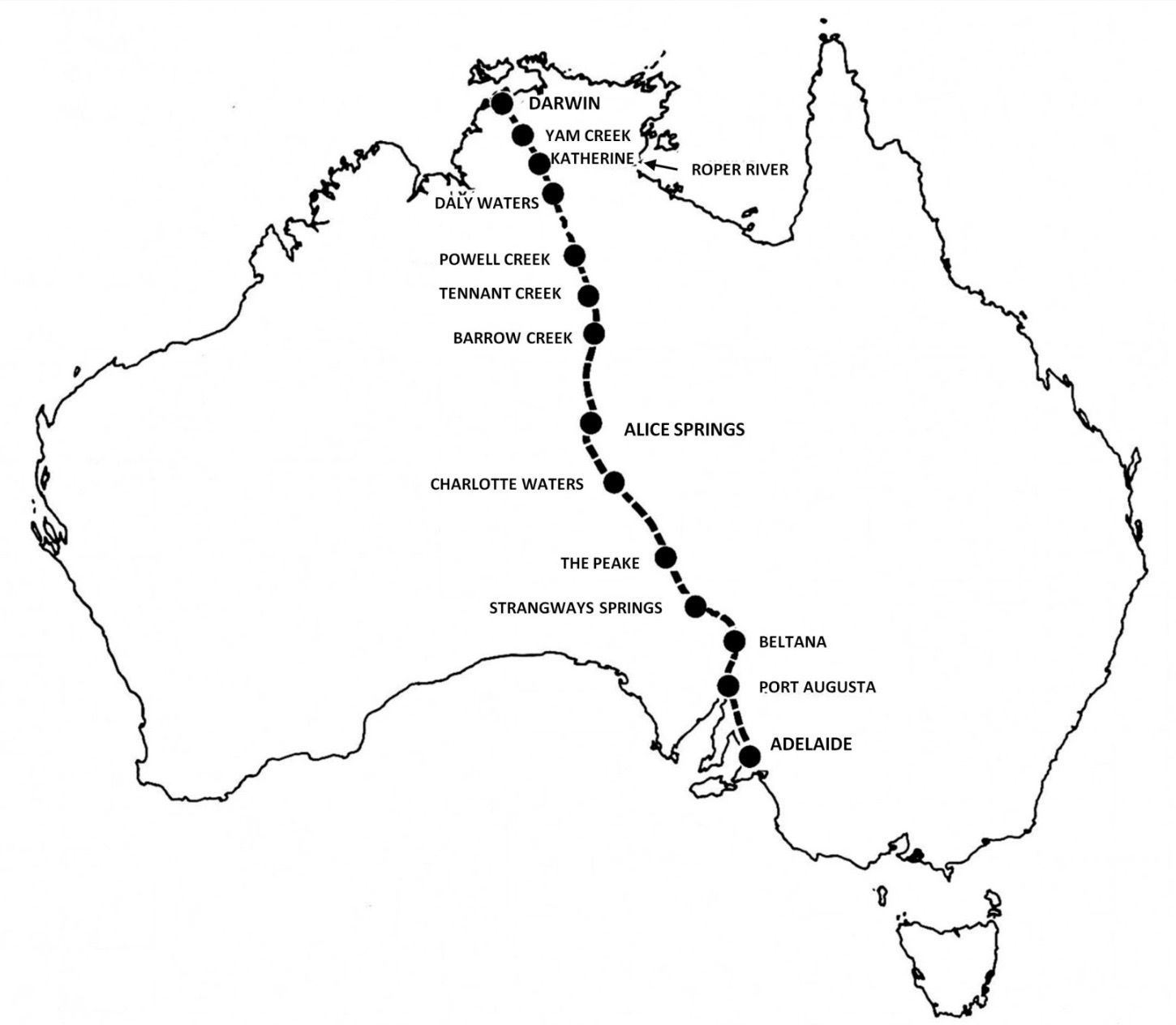

Finally, in 1870, the South Australian government agreed to construct the 3,200 km of telegraph line from Port Augusta in South Australia to Darwin. The stage was now set for the start of the biggest infrastructure project that Australia had ever undertaken, the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line. It seemed like a simple job: a single strand of wire transcribing a straight line across the continent. It would turn out to be anything but simple.

Building the line

Charles Todd, the South Australian Superintendent of Telegraphs, was appointed as the head of the Overland Telegraph Line project. Todd devised a timetable for completion of the immense project, and when the contracts were awarded, it was stipulated that it would take no more than two years to construct to construct the line.

Todd divided the route into three, 600-mile (970 kilometre) sections, with the northern and southern sections being handled by private contractors, and the central section to be constructed by his own Department of Telegraphs.

The line would comprise 36,000 poles placed 80 metres apart, with repeater stations, that would receive, amplify and relay the telegraph signals, to be built every 250 kilometres.

Construction of the northern section began in September 1870, and almost immediately ran into difficulties. The Wet Season began in November, with heavy rain which waterlogged the ground and made work impossible. The construction workers went on strike, complaining of rancid food and disease-spreading mosquitoes, and on May 3rd, 1871, the private contract was cancelled on the basis of insufficient progress. The South Australian government now had to construct an additional 700 km of the northern section of the line, along with the central section that they had already begun.

Meanwhile, the British- Australian Telegraph company was laying an undersea cable from Banyuwangi in Java, to Darwin. This cable was finished on the 31st of December 1871, in readiness for completion of the Overland Telegraph Line.

After almost two years, and seven months behind schedule, the two ends of the Overland Telegraph Line were joined at Frew’s Ponds, 640 kilometres south of Darwin, on Thursday August 22nd, 1872. Charles Todd had the honour of sending the inaugural message along the completed line. His message read:

WE HAVE THIS DAY, WITHIN TWO YEARS, COMPLETED A LINE OF COMMUNICATIONS TWO THOUSAND MILES LONG THROUGH THE VERY CENTRE OF AUSTRALIA, UNTIL A FEW YEARS AGO A TERRA INCOGNITA BELIEVED TO BE A DESERT +++

A communications revolution

The Overland Telegraph Line proved to be an immediate success. In its first year of operation, 4,000 telegrams were sent. Explorers used the repeater stations as bases for setting off to explore the still largely uncharted “Inland” of Central Australia. Prospectors reported their golden discoveries via telegraph, setting off gold rushes across the continent; station owners received news of prices on the London Wool Exchange as their flocks radiated out into the Outback.

The Singing Line

These days, with our cell phones, internet, satellite communication, and instant access to as much information as we need, it's hard to imagine what a great leap forward in technology the Overland Telegraph Line represented. Australia was now connected to the rest of the world. News, stock exchange reports, wool prices, military dispatches, and gossip could now be conveyed from Britain to Australia in just a few hours, rather than the months and months that it previously taken.

The Overland Telegraph Stations Today

The OTL ceased carrying international telegraph messages in 1935. By then, more advanced communications technology had superseded it. During World War Two, extra cross-arms and wires were added to the poles along the line so that it could be used for telephone communications, but even these were soon obsolete.

As radio, fibre optic cables, and satellite phones replaced the traditional analog systems, the wires were stripped from most of the line, and the repeater stations were abandoned.

As well as those odd, lonely poles in the deserts, the old repeater stations - such as the one at Peak Station on the Oodnadatta Track - can still be seen: forlorn relics, windowless and empty. However the Overland Telegraph Station at Alice Springs has been fully restored to how it would have looked in its heyday, when if formed part of the long, copper wire connection between Australia and the rest of the world.

So before you set off on your adventures in the Australian Outback, accompanied by your cellphone and your GPS data, pause at the station and reflect how far the world of telecommunications has come from the days of the Aboriginal songlines, and the messages singing in the wires of the Overland Telegraph Line.