Life is a whole, and luck is a whole…

– Winston Churchill, My Early Life.

At Sassoon Dock, the fishing boats lay moored in a tight jumble of keels, masts, rigging and flags. The foetid water, where it showed between the wide-beamed, hand-built boats, was grey-black, oily, stinking. In the shaded alcoves, slippery with fish guts, dog shit and rubbish, fish-wives squabbled over tidbits and sharp-eyed birds prowled reverentially looking for a meal. A navy helicopter, grey and incongruous, took off from the naval base beside the dock. The gay triangular flags, blue, green and orange, flapped rhythmically in the hot wind. Beyond the gate, with its squat, red-brick clock tower, Mumbai roared.

Along the waterfront, fishing boats fresh in from the Arabian Sea were unloading their catches of mackerel. The fish, shiny and bright like newly-minted silver coins, were loaded into baskets in the boats’ holds then hoisted up to the dock along a human chain. The last man on the boat, the strongest man in the crew, tossed each basket up to a waiting catch-man, who caught each basket nimbly and handed it to others who emptied them into yellow boxes. Hangdog cats, wafer-thin dogs, greasy-looking birds and scrawny crones competed to grasp any fish that spilled from a basket. No one begrudged these beggars their meagre spoils. The bounty of the sea was to be shared, Inshallah, with both the fortunate and the unfortunate.

Constructed in 1875, the Sassoon Dock was Mumbai’s first “wet dock”, a place where ships could be unloaded within a pool secured by lock gates. It was built on reclaimed land by David Sassoon & Co., a trading firm established in 1832 by David Sassoon, a Bagdhadi Jew who had relocated to Mumbai (or Bombay, as it was called) to trade in precious metals, spices, gum, wool and wheat. The company also helped establish the cotton trade between India and Britain, but Sassoon soon realised that the real money lay in Opium.

By the early 1870s, David Sassoon & Co. handled around 70% of the Opium traded between India and China, which it transported in its own fleet of Opium Clippers: fast sailing ships that could make the return voyage in the fastest possible time. By purchasing unharvested opium directly from the farmers who grew it, the company was able to undercut other British opium suppliers who purchased their opium from middlemen. The Holy Trinity of British trade in the mid-nineteenth century, Opium-Silver-Tea, made Sassoon a fortune.

But in addition to its association with the Opium Trade the Sassoon Dock was the scene of an incident in 1896 which may have shaped the entire destiny of the Western world during the Twentieth Century.

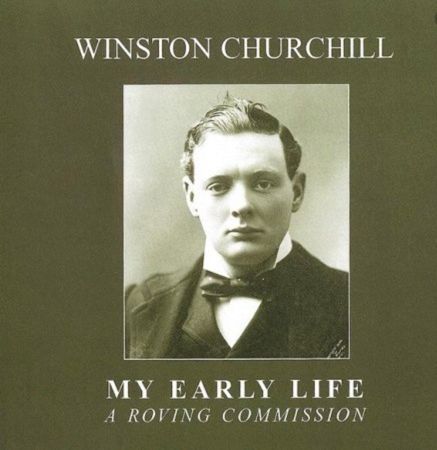

In November of that year, a young Winston Churchill arrived in Bombay to take up a three-year posting with his regiment in India. As he stepped ashore from the small boat which had conveyed him from the troop-ship that had borne him out from England, Churchill reached up and took hold of an iron ringbolt set into the side of the dock. As he prepared to pull himself up, the boat lurched on the water and Churchill wrenched his shoulder, tearing the ligaments holding the joint together and giving him an injury that would affect him for the rest of his life.

The injury meant that he could not wield a cavalry sabre, the weapon of choice for all mounted soldiers at the time. So Churchill purchased a Mauser pistol to use as his preferred weapon, a decision that would, perhaps, save his life a few years later during the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan.

In his memoir My Early Life , Churchill wrote of the incident at Sassoon Dock.

“This accident turned out to be a serious piece of bad luck. However, you can never tell whether bad luck may not, after all, turn out to be good luck. Perhaps, if, in the charge at Omdurman, I had been able to use a sword instead of having to adopt a modern weapon like a Mauser pistol, my story might not have got so far as the telling.

“One must never forget that when misfortunes come, that it is possible that they are saving one from something much worse. Or, that when you make some great mistake, it may serve you better than the wise decision. Life is a whole, and luck is a whole, and no part of them can be separated from the rest.”

Down in the dock, the fishing boats scraped and knocked together. The rigging tapped in the wind and the flags snapped and fluttered. I turned from the docks and walked out into the Colaba Market. Behind me, like Churchill’s ghost, a dog howled.