The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.

– L.P. Hartley, The Go-betweens

I thought I would die in Varanasi. It wasn’t the relentless, ubiquitous filth. It wasn’t the jostling, wild-eyed crowds celebrating the festival of Mahashivaratri. It wasn’t the cloying smoke of the burning ghats or the constantly spitting people. It wasn’t even the storm that cut the power to the city and smote the banks of the Ganges with detonations of thunder and jagged blasts of incandescent lightning. It was none of those things. In fact, I didn’t even think that I would actually die in Varanasi. I just appropriated that line from the 1920s-era travel writer HV Morten, who began his book In Search of England with the line “I thought I would die in Palestine”, in order to add drama.

But what caused me the most anxiety in Varanasi, and, indeed, throughout my journey to India, was the realization, final and irreversible, that I was no longer a traveller.

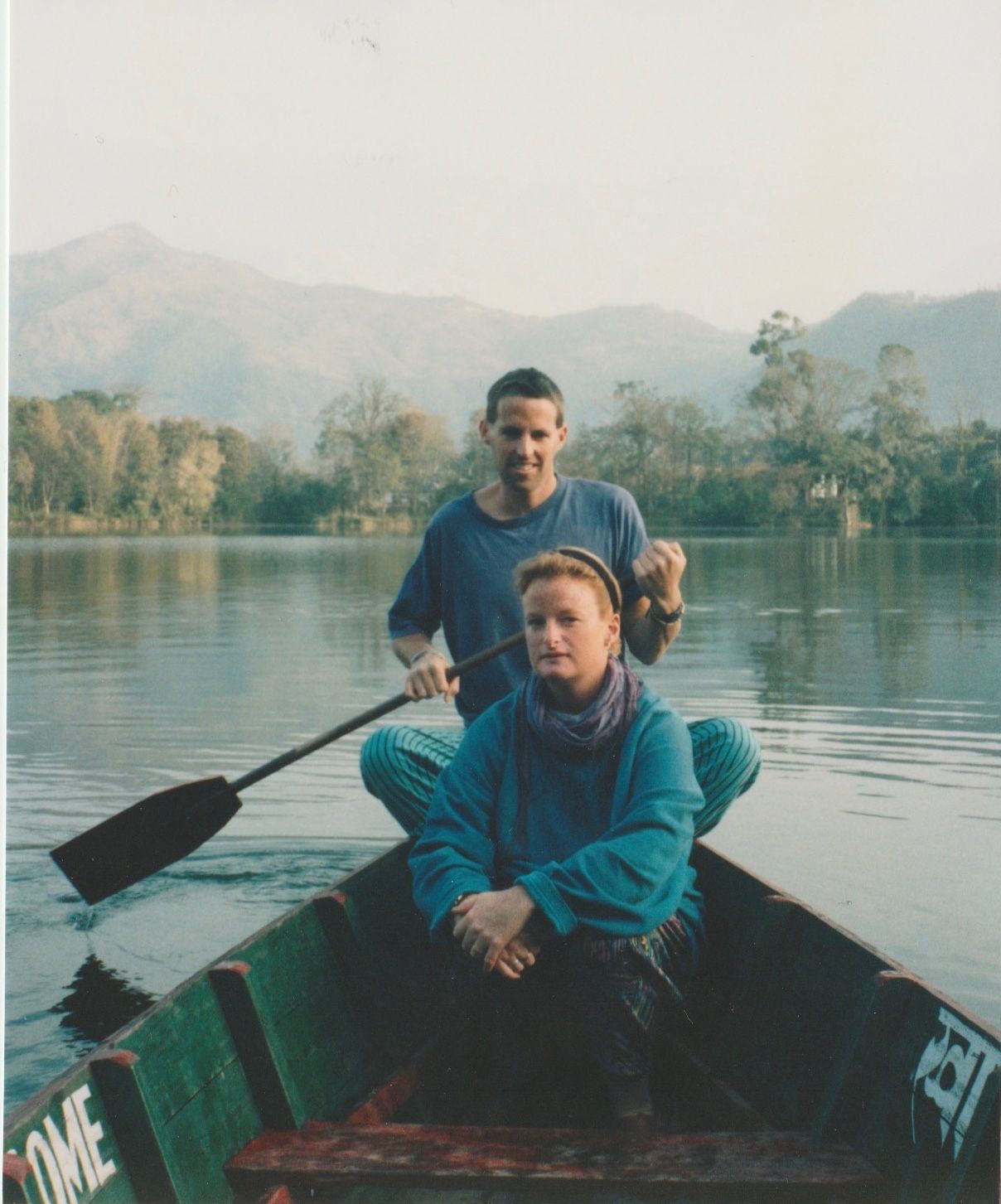

Between September 1988 and November 1994, my girlfriend Linda and I travelled the world. Our generation were born in the sweet spot of time (1963-1968) between the coddled Baby Boomers and the cynical Gen-Xers. And for a decade or so, from the mid-eighties to the mid-nineties, the world was our playground. And we travelled hard. During the course of our adventures we visited 35 countries on four continents, worked in pubs and factories and on farms, got engaged in Vienna, married in New Zealand, and lived the life of gypsies out in the world.

We weren’t tourists: we were travellers. We revelled in hardship. We took risks. We changed money with shady dealers in African back alleys. We raced floods and avalanches in the black gorges of the Indus Valley, where the river slices through the Karakoram Mountains in the north of Pakistan. We lay on jewelled Indonesian beaches and smoked hash beside the funeral pyres of Varanasi. We rode third class, ate on the streets and slept in dirty, dirt cheap flophouses with only the billowing, diaphanous folds of a mosquito net between us and malaria. We negotiated tricky roads in dangerous territory and, occasionally, lolled in comfort in 5-star hotels where the colour of our skin gave us exclusive entry. We haggled over every last rupee, shilling and dirham. We were on the road. Nothing else mattered.

Then home. Reality. Careers, kids, a mortgage. All the good stuff. The settled life. Twenty-eight years passed. And then, I was back in Asia, with a backpack, a list of destinations, and a notion that I would travel hard again. A wanderer in the Blue Rooms. A traveller.

But it was too hard. And I was too old. India was hot, squalid, crowded, unfathomable and relentlessly filthy. I ditched half my itinerary and moved up-market. I stayed in good hotels, took expensive, air-conditioned sleeper trains, navigated with Google Maps and rode Ola and Uber wherever I went. I didn’t die in Varanasi. I just let go of my old self. The traveller became a tourist. And that’s OK. The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.