Never mind those making promises of the afterlife;

Join us now, righteous friends, in this intoxication…

– Zeb-un-Nissa, Mughal poetess.

She was the love of his life. His favourite wife. Mother of his heir. To Aurangzeb, soon to become Emperor of the Moghul Empire, the greatest empire that India had seen, she was the world: a perfect pearl in a jewelled firmament. Her name had been Dilras Banu Begum. She had borne him four children. The eldest, Zeb-un-Nissa, would become a gifted poet. Their son, Muhammad Azam Shah, would one day succeed him, albeit briefly, as Emperor.

But in giving birth to their fifth child, Dilras Banu Begum died. Grief-stricken, Aurangzeb commissioned a monumental tomb for her. It would be the only great building that the Emperor would build during his reign. A pious, austere and parsimonious Muslem, Aurangzeb had little time for monuments. To him, the great works of his predecessors – Akbar’s Fatepur Sikri, Shah Jahan’s Taj Mahal – were of little use. To him, creating illuminated copies of the Qur’an were of much more significance in the temporal world. His late and beloved wife, however, deserved a monument that was of suitable grandeur: a monument to Aurangzeb’s conjugal fidelity. And so, Aurangzeb designed and built the Bibi Ka Maqbara.

Stepping through the vaulted arch of the marble entrance gate I was immediately transported back to the day in 1992 when I first saw the Taj Mahal. Flanked by four slender minarets, the perfect dome of the Bibi Ka Maqbara, perched lightly on its dias of polished marble and red sandstone, is an almost exact of its larger and more famous contemporary.

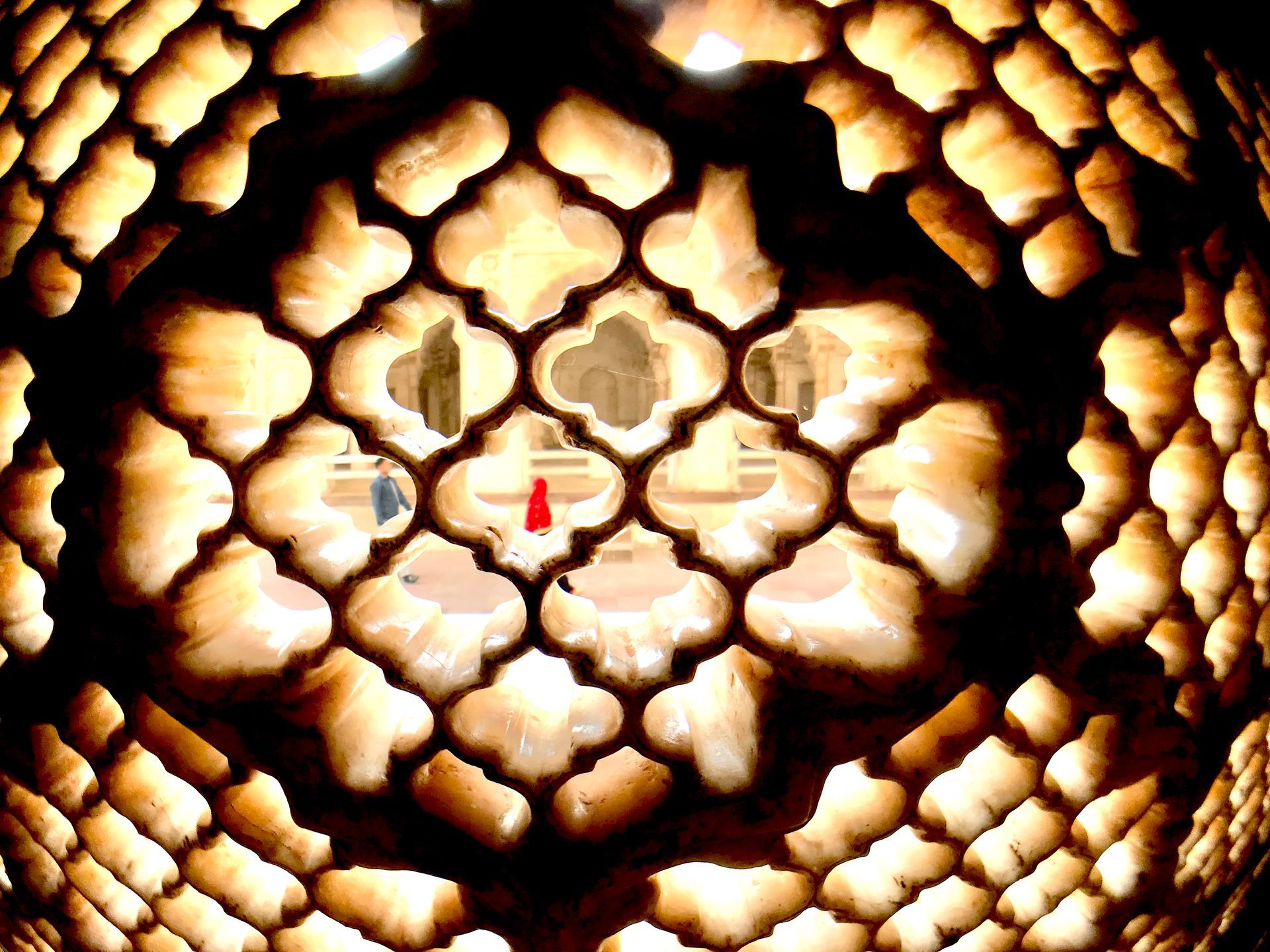

Crowds of afternoon visitors thronged the flagstones and side gardens. A long marble water-garden, dry now but still perfectly proportioned, drew me forward. I climbed a set of stone steps, removed my boots and entered the cool, dim inner sanctum. A cool breeze flowed through the interior from delicate lattices, carved from single slabs of pure white marble, set into four alcoves. Below the level of the floor, and covered by an intricate silken blanken, lay the tomb of Dilras Banu Begum: a perfect pearl intombed forever within her marble shroud.

I sat on the edge of the west alcove, savouring the zepher of wind flowing through the lattice and watched the crowds walking reverentially around the tomb, clockwise, and tossing coins for luck down onto the Begum’s tomb. Gravestones and monuments are for the living. They are no use to the dead. The Bibi Ka Maqbara is a living, breathing tomb: an incarnation in marble of the words of Zeb-un-Nissa, Aurangzeb’s daughter: Never mind making promises of the afterlife; join us now in this intoxication.