I wish I had invented blue jeans…

– Yves Saint Laurent

It was an uprising in blue. The Nil vidroha , or Indigo Revolt, was a peasant movement started by indigo farmers in Bengal in 1859. Tired of being exploited by landowners and money-lenders, the farmers went on a rampage, taking their cue from the recent Indian Mutiny. Atrocities were committed. Property was destroyed. The usual cycle. The Government sent in troops.

Indigo is a colour that has always signified wealth. Because of its relative scarcity, the dyes made from indigo were used only for high quality textiles such as the tagelmust headscarves worn by the Tuareg of the Sahara and the garments worn by Japanese nobility during the Edo Period (1600-1868). Isaac Newton described indigo as one of the primary colours in Lectiones Opticae , his 1765 description of the rainbow.

The indigo plant, Indigofera tinctoria , had been exported from India in small quantities along the Silk Route since antiquity. Pliny the Elder mentioned India as the source of indigo. Its name derives from the Greek word indikon , which moved to the Latin INDICUM and thence to Italian and English.

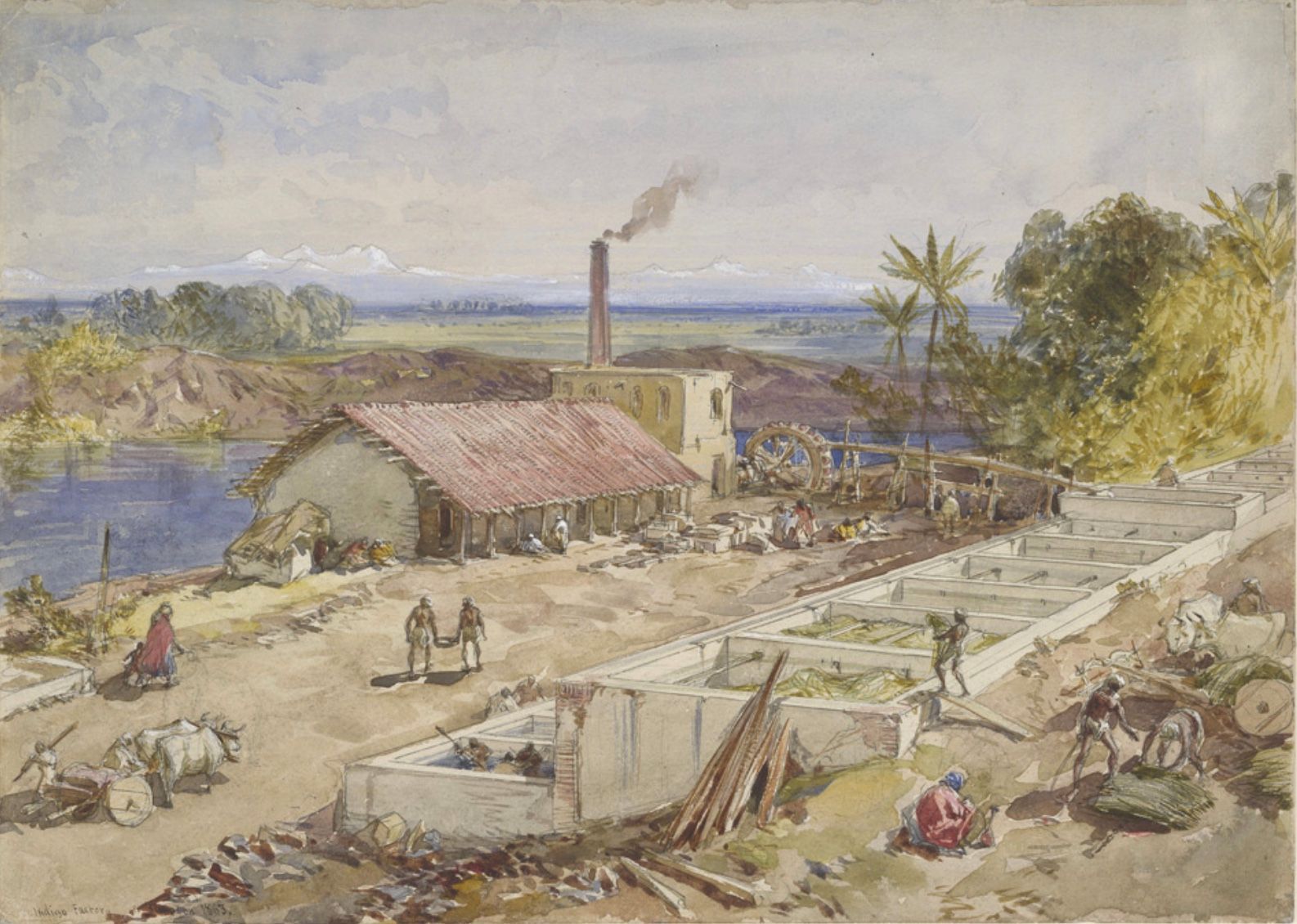

The planting of Indigofera tinctoria in the modern era began in the Indian state of Bengal in 1777 when a French farmer named Louis Bonnard began cultivating the plant at Taldanga and Goalpara, near present-day Kolkata. The demand for indigo in Europe, driven in part by its use in a new type of heavy-duty serge cloth being manufactured in the French town of Nimes, made it a highly profitable crop.

European planters (wealthy farmers who rented land from the land-owning Indian Zamindars ) persuaded their small tenant farmers to plant indigo instead of food crops. They provided loans to the farmers for seed and equipment but charged such high interest rates that the farmers could never repay the loans. When the crops were harvested, the planters and their Indian dealers paid the farmers meagre prices: only 2.5% of the indigo’s true market value. When the farmers were unable to repay their loans the planters resorted to the destruction of the farmers’ houses and property.

An Act of Government, passed in 1833 by the corrupt and easily-bought East India Company (who governed India until 1858) strengthened the position of the planters and the Zamindars. The Bengali middle-class, however, supported the peasant farmers in their plight. The play Nil Darpan , by the Indian playwright Dinabandhu Mitra was instrumental in garnering support for the farmers. The play was banned by the East India Company but has subsequently been seen as being an essential part in the development of theatre in Bengal.

The Indigo Revolt began in the towns of Gobindapur and Chowgacha (now in modern-day Bangladesh) and spread rapidly across Bengal. A number of planters were tried and executed by hastily-convened kangaroo courts. Indigo depots were burned down. The planters and their families fled. Many Zamindars were murdered.

After the initial surprise offensive by the farmers, the government collected itself and the revolt was ruthlessly suppressed. Large forces of government (ie East India Company) police and soldiers were dispatched to Bengal. The revolt’s leader, Biswanath Sardar (described by later historians as a “heroic, Robin Hood-like figure) was tried and hanged by the British.

Despite atrocities committed by both sides, the revolt remained popular with the Bengali middle-class. Even some of the Zamindars

supported the peasant farmers’ cause. When the violence died down, the Government set up The Indigo Commission in 1860. Its aim was to put an end to the planters’ oppression of the small farmers. Its report noted that, prior to the end of the revolt, “not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.”

Nothing remains today of the Indian indigo industry. Indigo dye is produced synthetically and the old indigo warehouses of Bengal are all gone. But one thing remains. Those blue jeans you are wearing. They are made using a heavy cotton cloth woven from thread dyed with indigo. That cloth originated in the french town of Nimes. It’s called serge de Nimes. We call it denim.