The air is humid and a few spots of rain begin to fall.

Morning at Howrah Station. As the Doon Express pulls into Platform 5, I look out through a scratched and grimy perspex window at the sun, rising pale and wan, through a haze of smoke and mist. Porters shift loads of hessian-wrapped freight along the platform, dodging and weaving among the throng of people disembarking from another train on the opposite side. The train stops with a gentle lurch. I swing up my backpack and stand in the aisle waiting for the doors to open. A steward moves through the carriage collecting rubbish. I shuffle forward with the rest of the passengers and step out onto the platform

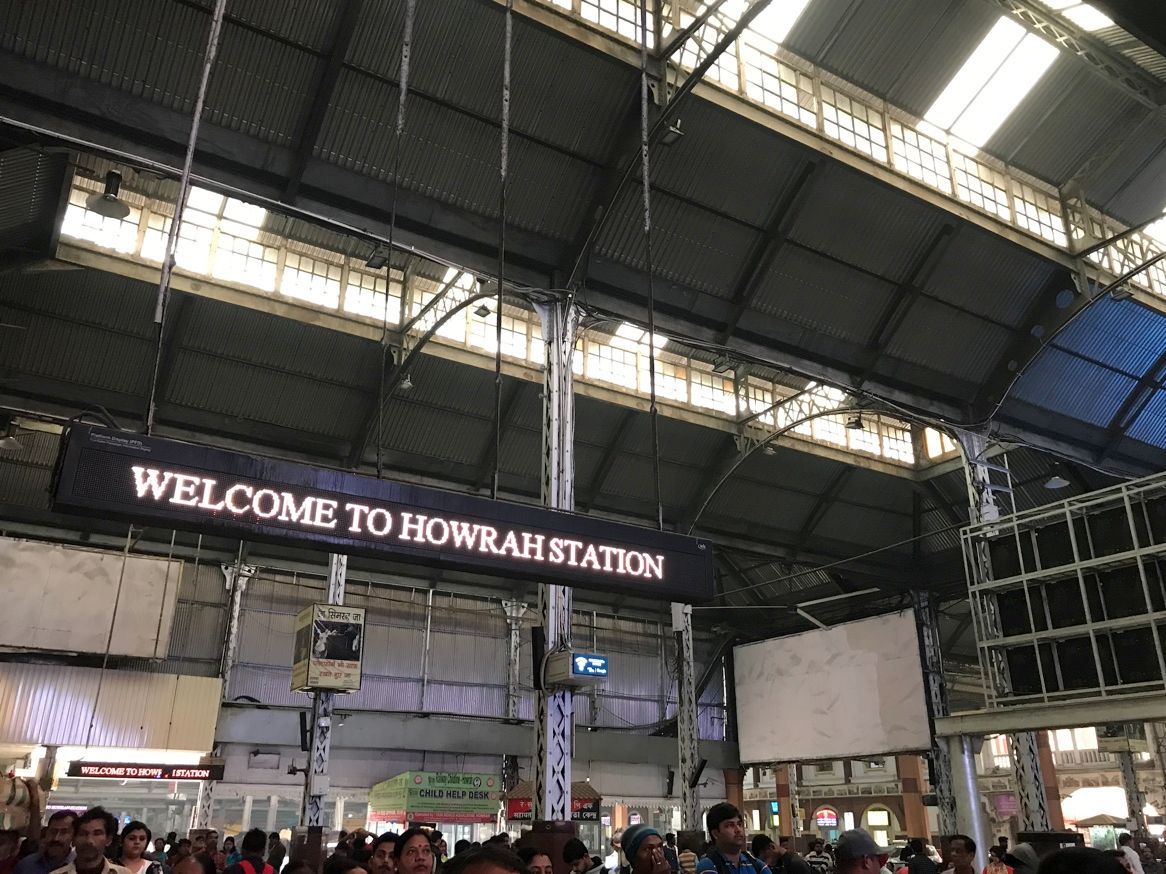

The cavernous interior of the concourse is surprisingly clean and uncrowded. This is one of the busiest railway stations in the world yet at this hour – 7am on a Monday morning – the main rush hours are yet to begin. First completed in 1854, Howrah Station is also the oldest railway station complex in India. Two million people pass through the station daily. Its 23 platforms handle more than 600 trains each day. The tracks leaving the station branch out to 1373 other stations all over India.

As I make my way towards the exit, I remember Paul Theroux’s description of the station when he arrived here in 1978. He described a Dickensian gloom peopled with ragged figures asleep in crepuscular corners. I saw smartphone screens, businessmen and colourful saris. The walls are painted in somewhat garish shades of yellow and purple. There are armed police patrolling. No one bothers me.

Outside the station I thread my own way through the clamorous bustle of the bus station and up onto the steel lattice of the Howrah Bridge. The air is humid and a few spots of rain begin to fall. The wheels of an endless stream of cars and trucks rattle on the deck plates. Pedestrians, many carrying bundles on their heads, line the walkway on the outside of the bridge. A few beggars sit listlessly against the railing, their hands out. I donate a fifty rupee note each to a couple of them and set off across the bridge.

Kolkata is India’s seventh most populous city. The city itself has a population of 4.5 million but with the inclusion of its surrounding metro area that number grows to 14 million. Founded in the late seventeenth century by the East India Company as a fortified trading post, Calcutta (the Anglicized name was used until 2001) was the company’s administrative centre for more than one hundred and fifty years. When the British Government took over the running of India from the company following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Calcutta became one of the jewels of the British Empire.

On the far side of the bridge I descend the curving abutment path into the decayed chaos of Mahatma Gandhi Road. A swarm of yellow taxis hurtle past, their drives peering out at me in the hope that I might be looking for a lift. I pause on a corner beside a cluster of stalls and order an Ola. While I wait for it to arrive I chat to a stallholder about the cricket. The Second Test between New Zealand and India has just commenced back home. I ask him what the score is and he turns to the sports page of the Times of India which he has spread out before him on the wooden table where his wares will soon be displayed. The Indian team elected to bat first; the score is 20 for nothing.

My Ola arrives – another battered white Hyundai – and I clamber into the back seat. I am sweating and my cold weighs heavily on my head. As the driver threads his way in and out of traffic, dives down narrow back streets, I half doze. On Chowringhee Road we join a flowing river of vehicles then decant into a side street and pull up outside the Peerless Inn Hotel.

I pay the drive twice the quoted fare for his efficient driving. A footman opens the door for me. Begging children appear as if out of thin air. The hotel towers overhead. Inside it is quiet and warm and busy. My room isn’t ready but the concierge says I can sit in the lobby until it is. I order a latte from a tiny, spotless stall. The girl brings it out and places it on the glass table in front of me. It tastes amazing. The concierge comes over and offers me an early check-in package for an extra R1,000 including a buffet breakfast.

My suite is a bit extravagant for a solo traveller. It has three rooms. Everything is upholstered with pale green baize. I shower and descend to the Oceanic Room. I am starving. I eat fresh pineapple, bread rolls, two poached eggs, and toast with butter and marmalade. The waiter brings me a pot of English Breakfast tea.

I sit at a table beside a wide plate glass window. Outside, it is raining. The raindrops splash onto the verdant foliage of palms and ferns planted in a garden. Inside, I listen to a group of American tourists discussing their day. They don’t seem to know what they will be doing but something has been organised for them. I plan to go out and find a café and maybe visit the Park Street Cemetery. But first, I need to sleep.