…their brick bones stripped of stucco skin.

Beyond the pedimented gateway, the roar of traffic on Park Street fades to a low, susurating murmur. The flagstone path is slippery with moss and from the gentle rain tapping on the blue and red umbrella that the gatekeeper has lent me. The path runs directly from the entrance to the back of the cemetery, intersecting at regular intervals with the grid of other paths laid out with geometric British precision.

I am surrounded by a garden of rainforest greenery and stone. Tombs of sandstone and brick stand in tiered rows between the trees. Their minarets and columns, domes and obelisks are rimed with moss and lichen. Acid rain has etched the limestone with black, cancerous stains. Some of the tombs are crumbling, their brick bones stripped of stucco skin. A litter of leaves and palm fronds lies scattered across the ground.

Yet amid the decay and dampness there is a quiet dignity in these silent memorials. Their plaques of polished marble tell poignant stories of great achievement and lives cut short; of devoted and unswerving service to John Company; of camaraderie and bravery; of love and loss. And even though these memento mori are almost two hundred years old, their stories still seem fresh and vital.

Opened in 1767, the Park Street Cemetery is one of the largest non-church Christian cemeteries in the world. Its tombs and monuments have stood in silent remembrance for more than two hundred years while the world around them changed. It remained in use until the 1830s.

The tomb of Hindoo Stuart stands beneath a magnolia tree in a back corner of the Park Street Cemetery. It is a smallish domed structure built from a combination of stucco-coated brickwork and black marble decorated with carvings of various Hindu deities. It’s inscription reads:

MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES STUART

(KNOWN AS HINDOO STUART)

1758-1-4-1828

QUARTERMASTER OF THE 1st BENGAL

EUROPEAN REGIMENT & LATER COMMANDED

THE 10th ANDIS REGIMENT

Born in Ireland, Stuart was an officer in the East India Company and was well known throughout the Company as being one of the few officers to embrace Hindu culture. Stuart was not only fascinated by Hinduism, he saw it as the most comfortable way in which to live in the torrid, crowded, disease-ridden conditions of the subcontinent. He encouraged the English ladies of the Company to adopt the “elegant, simple, sensible and sensual” saris worn by Indian women instead of the heavy (and heavily engineered) iron busks worn by the white Memsahibs. He described these as “the prodigious structural engineering European women strapped to themselves in order to hold their bellies in, project their breasts out and allow their dresses to balloon grandly up and over towards the floor.”

When Stuart died, on March 31st, 1825, he was buried in the South Park Cemetery in a tomb styled on a Hindu temple. But although he had adopted Hinduism as his religion, ha had not completely abandoned Christianity, describing the deity Krishna to be: “the spirit of God who descends upon Earth for the benefit of mankind.”

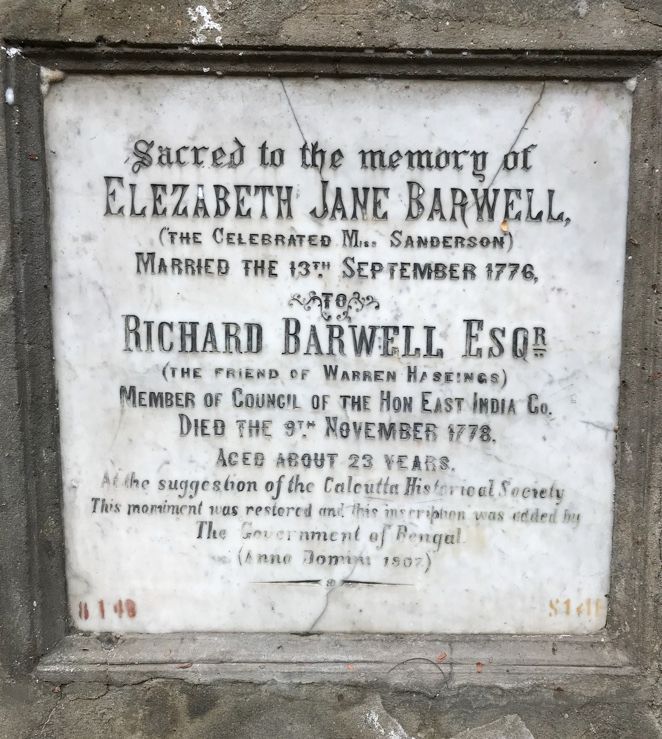

Beyond the screen of foliage and branches I can see the glass and steel towers of the city. A pair of rabbits scamper across a patch of green grass inside a quadrangle of tombs. Funereal crows, like black-winged sextons, gurgle and squawk in the trees. I stop beside the middle tomb in a row of three: squat, triangular obelisks. The white marble plaque inset into its base has an intriguing inscription which reads:

Sacred to the memory of

Elizabeth Jane Barwell

(The celebrated Miss. Sanderson)

Married the 13th September 1776 to

RICHARD BARWELL. Esq

(the friend of Warren Hastings)

Member of the Council of the Hon. East India Co.

Died the 9th November 1778.

Aged about 23 years.

There is no indication as to what Miss Sanderson did to become “celebrated” but in the torpid, breathless, straight-laced (on the surface, at least) world of Kolkata in the early 19th century, I imagine it involved something steamy. As for Warren Hastings, he was the energetic Governor of Bengal who succeeded the psychopathic Clive in 1875. To be a friend of Warren Hastings”, as Miss Sanderson’s husband was, according to their plaque, was to be admitted to the highest echelons of power in the East India Company.

As I walk along the pathways I feel as though I am moving in slow motion, like a voyager returning from a distant galaxy to find that time has slowed down. I have a pocket full of technology and yet I am surrounded by the remains of a world that no longer exists. I stop to rest on the step of a colonnaded tomb surmounted by a graceful sandstone cupola. I take out my communicator and update my social media. I have a story to tell: a story that I discovered back in December while sitting in a café researching my trip…