The British never set out to conquer India…

It is sometimes said that Britain obtained its empire in a fit of absentmindedness. It wasn’t so much a desire to conquer and rule that motivated the British. Rather, it was more of a slow acquisition of territories by default: a kind of global game of pickup sticks where the sticks were colonies, countries, and resources. At its zenith, the British Empire extended over 25% of the globe and contained within it a similar percentage of the world’s population. In school atlases, the pale pink wash denoting the countries and territories of the Empire was familiar to every pupil for generations. The sun never set on the British Empire and it was always time for a G and T somewhere. And the jewel in the Empire’s crown was India.

The British never set out to conquer India. It was actually a small company, housed in a nondescript building on Leadenhall Street in London, that set in motion the events that would lead to the control of the Empire’s greatest asset. That institution was called The East India Company.

On the 22nd of February, 1599, a group of merchants and financiers convened in a pub called the Nags Head Inn opposite the church of St. Botolph in Bishopsgate, London. Their aim was to establish a company to trade in spices from the East Indies, a trade dominated at that time by the Dutch and the Portuguese. Armed with a Royal Charter guaranteeing them exclusive access to all the seas and countries east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan, the East India Company, as it came to be known, began trading with the kings and rulers of Asia.

The risks involved were huge. Many ships were lost, along with their crews and cargoes. Piracy, danger, hardship and violence were the only factors that could be relied upon. But the profits were enormous. As its trading links with the rest of the world expanded, the company began gradually to establish footholds on the continents and territories it traded with. In India, the company’s first trading post, or factory as such outposts came to be called, was established at Surat on an inlet of the Arabian Sea on the western coast of the subcontinent in 1612. Bombay (now Mumbai) was added in 1668 and further factories were established around the entire coastline of India.

The company’s greatest factory was established on the Hooghly River, an exit tributary of the Ganges, in 1698. There were three villages in the area – Kalikata, Gobindapur and Sutanuti – and the town that grew up around them took its name from one of them: Kolkata. Initially, the company built a fort they named Fort William on the eastern bank of the Hooglhy at Kolkata.

There were frequent skirmishes with the French in the region and the fort and factories were sacked by the Nawab of Bengal, resulting in the infamous Black Hole of Calcutta incident, in 1756. But the town of Kolkata (or Calcutta as the British called it) survived and grew to become the seat of power for the company.

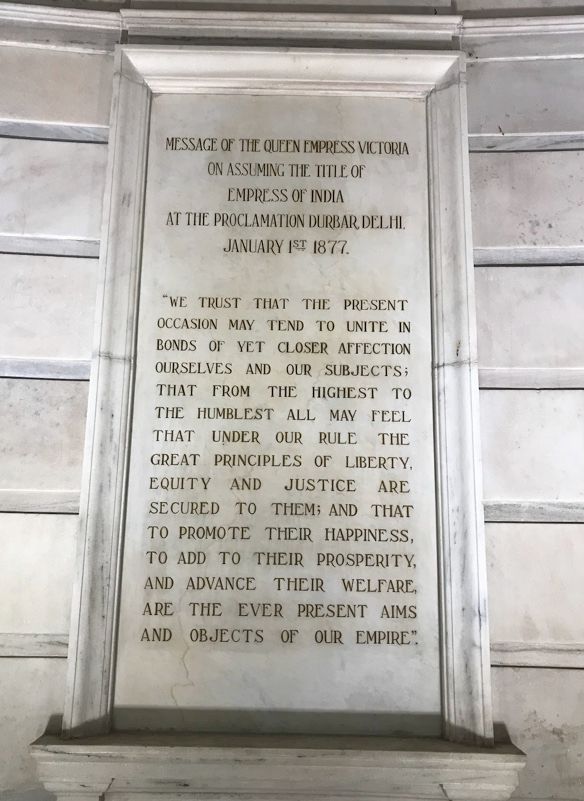

At the Victoria Monument, a vast domed marble edifice surrounded by fountains and gardens in the centre of Kolkata, I came face to face with the East India Company in the form of a statue. The subject stood resolute on its marble plinth. His eyes, set in a strong face with a rigid jaw and a slight scowl, stared rigidly out into the distance. In his left hand, he held a half-rolled scroll of documents; his right hand rested lightly on his sword. On the square plinth beneath his booted feet was carved one word: CLIVE.

Robert Clive (1725-1774), First Baron Clive, KB, FRS was the man who took the East India Company from a predominantly commercial trading company to a full-fledged military power with suzerainty over the entire Indian subcontinent. Prior to the Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which the company’s forces under the command of Clive defeated the Nawab of Bengal, the East India Company (or John Company, as it was informally known) had concentrated on trade. For one hundred and fifty years the company had been content with buying goods – predominantly spices and cotton – for shipment back to England. But Clive changed all that.

For the next ninety years the East India Company treated India like a cash cow, milking it of resources and establishing the highly dubious trade in opium which gave rise to the mid-century conflicts with China known as the Opium Wars. But all was not well in John Company. Since its zenith in the 18th century, the company’s profits had steadily declined. Its increasingly patrician (and, in many cases, oppressive) rule of the subcontinent had grown more and more unpopular among Indians.

By the time of the Battle of Plassey, the EIC already had a substantial army, composed mainly of Indian troops known as Sepoys. The troops were used to enforce the company’s often unpopular regulations, to protect its interests and assets and to generally ensure that what the company wanted, the company got. After Plassey, the company essentially became the rulers of India.

In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, in which the sepoys rose up against their oppressors, the British Government took over control of the company. By then, the East India Company was in decline. Its assets were nationalised by the British Government. Its army, possessions and all of the machinery for administering and controlling India were ceded to the Crown.

John Company was finally dissolved on June 1st 1877. In an editorial, The Times commented that:

It accomplished a work such as in the whole history of the human race no other trading Company ever attempted, and such as none, surely, is likely to attempt in the years to come.

In my travels across India I encountered the legacy of John Company, and its successor, the British Raj everywhere I went. In the buildings, the railways, the bureaucracy; in the vast self-indulgent monuments, in the cemeteries, in the layout of towns and in the place names.

In the 1980s, a group of Indian entrepreneurs bought the rights to the name East India Company and established a clothing brand under that name. The company traded until the early 1990s when it too folded. In 2010, the moribund corporate name was once again acquired as the trading name for a clothing brand. Today, a British company trades under the name The East India Company, London. It sells tea, coffee, chocolates, nuts and spices. John Company still lives. It didn’t set out to create an empire. But it did.

On the square plinth beneath his booted feet was carved one word: CLIVE.