…the tomb of Nithar, lies reflected in the shimmering pool.

In Allahabad I find a secret garden. I have been walking for hours: exploring the parks of the city’s centre, the exquisite domed buildings of the University, the sad, barricaded, derelict cathedral. I have fallen asleep on a concrete bench beneath a shady tree in Prince Alfred Park, and followed back streets through leafy suburbs. Now, I stand before a high wall of betel-splattered stucco. Inside, under the high blue dome of the sky, lies Jahangir’s garden.

Beyond the vaulted gateway, where vendors sell chai, puris and cold drinks, and a barber plies his blades on a worn wooden chair, a geometric pattern of flagstone pathways, lined with graceful palm trees leads towards a walled inner garden. Sprinklers shimmer in the midday sunlight. Families picnic on colourful blankets laid out in shady spots. Young men pose theatrically for photographs.

Inside the walls, three sandstone tombs, each of differing design, stand in a line flanked by gardens and flagstone paths. Begun in 1606, the tomb complex, known as the Khusrau Bagh, was designed by Aqa Reza, the court artist to the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. The first tomb to be constructed was that of Shah Begum, Jahangir’s wife, who had died by suicide in 1604. Distressed by the enmity between her husband and their son, Khusrau (who had tried to usurp his father’s throne), Shah Begum had swallowed an overdose of opium. Her three-tiered tomb, surmounted by a rectangular divan, draws its inspiration from Fatehpur Sikri, the Mughal’s capital city in Northern India built by the first Great Mughal Emperor, Akbar.

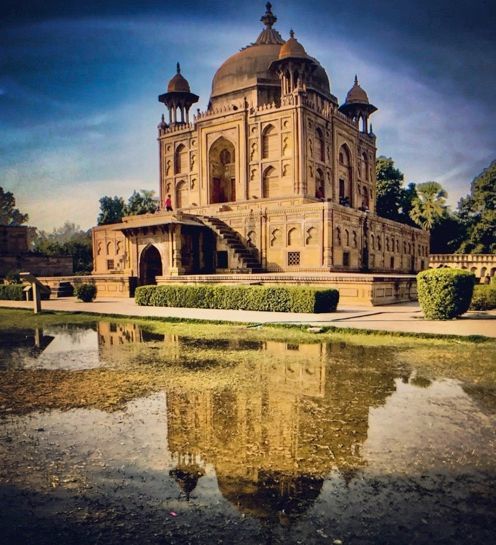

I follow a path along the outer wall of the garden. There are rows of pale roses planted along the edges. Beyond the wall, in a grove of fig trees, goats graze on fallen leaves. Crows gurgle in the undergrowth. A couple of older men, the complex’s groundsmen perhaps, sit on a bench in the shade while a hose spills water onto a patch of lawn in front of them. The second tomb, the tomb of Nithar, Jahangir’s daughter, lies reflected in the shimmering pool.

The tomb stands on an elevated platform recessed with alcoves decorated with fretted stonework. Its central dome is flanked by four delicate cupolas. Some of the alcoves are closed with heavy doors of dark red wood. A group of schoolgirls, clad in white saris with colourful sashes, sit in a semicircle on another patch of grass in front of the tomb of Nithar.

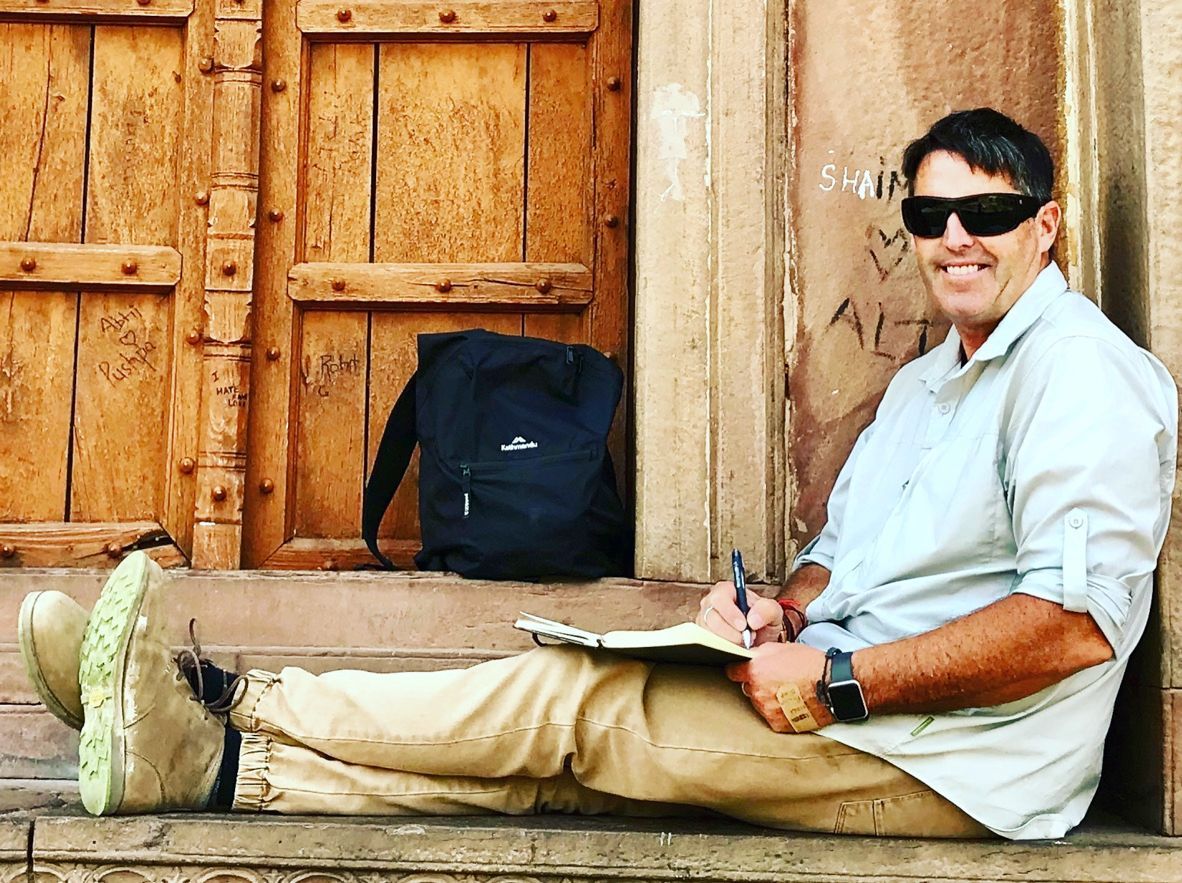

I climb a set of steps set into the plinth of Nithar’s tomb and sit on a sandstone ledge beside a carved wooden door inset with iron studs. Flights of pigeons circled the dome of the third and final tomb, the Tomb of Khusrau himself. Khusrau Mirza was the Emperor’s second son. He rebelled against his father in 1606 in a bid to succeed the Emperor Akbar as the ruler of the Moghul Empire but was defeated in the battle of Bhairowal. He fled to Kabul but he was captured and taken to Agra where he was imprisoned.

In the Moghul world, succession wasn’t simply a matter of the eldest son inheriting the throne from his father. Rather, siblings competed against each other with intrigue, patronage and outright violence until a winner emerged. It was often the case that the sibling who gained the upper hand would have the rest of his family – brothers, sisters, cousins – put to death in order to guarantee that there was no one left to threaten his position.

In 1607, Khusrau was blinded as a punishment for rebelling against his father. Then, in 1622, he was killed on the orders of his brother, Prince Khurram, who had succeeded the throne and taken the title of Shah Jahan: possibly the most famous of the Mughal rulers.

I sit on the cool stone of Nithar’s tomb writing my notes and watching the scene below. A group of young people chatter and run. Beside me, the heavy timber door is weathered and cracked. Graffiti has been scratched into its blackened and cracked surface. The iron hasps and bolts are rusted and bent. The slow, inexorable hand of time has worked on the tombs, etching the history of years into every surface. The flights of pigeons circle the tombs and settle, momentarily, on the domes and cupolas before erupting into flight again to circle, wheeling in the high blue sky above Jahangir’s garden.