Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai,

Whose doorways are alternate night and day.

How Sultan after Sultan with is pomp,

Abode his hour or two, and went his way…

And so I came, at last, to my final destination in India: the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata. I had wandered through the stone garden of the Park Street Cemetery, sat quietly in the grand neo-Gothic St. Paul’s Cathedral and walked along busy, crowded Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Road to the gardens of the Maidan.

The British loved to build. To them, as it was with most great empires, it was their buildings that spoke of their power, their cleverness, their capabilities. In the Victoria Memorial, the technology and vision that they had perfected over the previous century or so came together in what is, to me, one of the greatest buildings in the world.

Completed in 1926, the Victoria Memorial was commissioned by Baron Curzon, the Viceroy of India, as a monument to Queen Victoria, who had died in 1901. It was designed by the British architect William Emerson, who also designed the lovely blue-domed buildings at the University of Allahabad that I had loved so much ( see my earlier post The Blue Dome ), and its foundation stone was laid by the Prince of Wales, later King George V, on January 4 th , 1906. A public subscription was opened to pay for the building’s construction and the entire project was financed by donations.

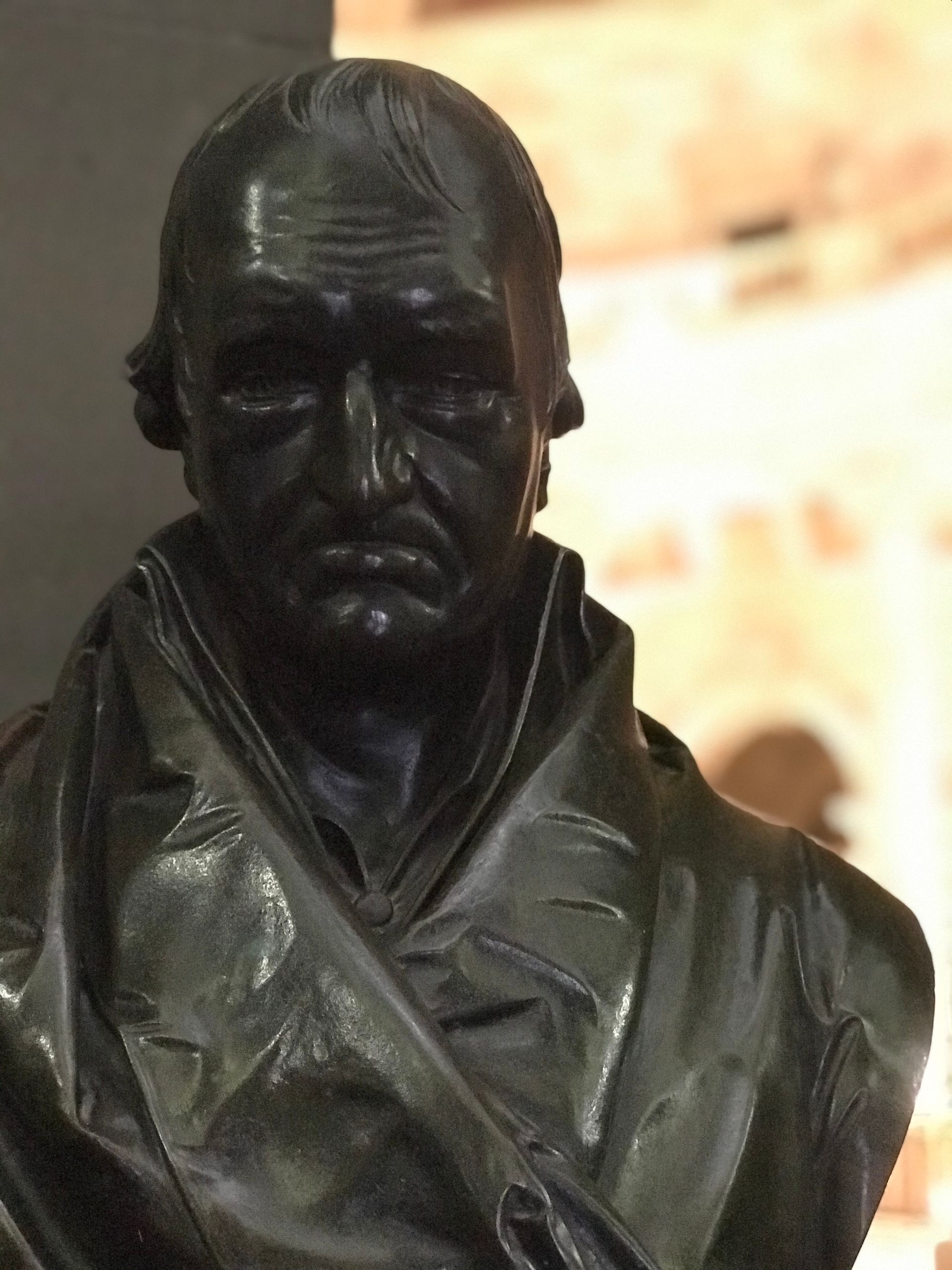

It was designed to be not only a fitting monument to Queen Victoria but also a museum: a place where future generations could come and experience the history and power of the British Raj. To this end, its anti-chambers and rooms were filled with paintings depicting the great moments of Indian history; with weapons used in the great wars fought by its rulers; and with sculptures of the great men who forged the Empire. As Curzon had put it:

Let us, therefore, have a building, stately, spacious, monumental and grand, to which every newcomer in Calcutta will turn, to which all the resident population, European and Native, will flock, where all classes will learn the lessons of history, and see revived before their eyes the marvels of the past.

But nothing lasts forever. By the time the monument was completed, the Raj’s seat of power had been transferred to Delhi. For all its grand colonial buildings, Calcutta had become a provincial capital. And the world was changing. The Great War had wrought rifts in the Empire from which it would not recover. The Empire was beginning to fade, just as the Persian poet Omar Khayyam had prophesied in his oft-quoted Rubaiyat:

Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai,

Whose doorways are alternate night and day.

How Sultan after Sultan with is pomp,

Abode his hour or two, and went his way…

These were words that Kipling had echoed in his poem Recessional , written to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. He foresaw, just as Khayyam had, eight hundred years before, that all empires will eventually fall, leaving nothing behind but the buildings that the sultans, the emperors and the kings had built in their own names.

I walked slowly around the perimeter of the building to its grand front entrance. A marble bridge, designed by Emerson’s assistant, Vincent Jerome Esch, spanned a lake of reflective green water. Atop the bridge, a sculpture of Queen Victoria, resplendent in the ceremonial robes of the Star of India. I took out my phone and recorded a Snapchat of what I was seeing.

And here she is, Queen Victoria, Empress of India, sculpted in bronze towards the end of her life when she was fat, half mad and clinging to life. And you’ve gotta hand it to the Brits. When they built, they built big. They liked to build these massive edifices that said “look at us, look how fucking good we are.” Of course the Germans also tried that during the nineteen thirties with those square, box-like, blocky buildings of Nuremberg and Berlin. But they just ended up looking stupid, overdone and megalomaniacal. The Victorians combined Mughal architecture with their high-tech construction methods and sense of scale and proportion in order to create buildings like this which still look beautiful a hundred years later.

Nearby, bas-relief panels of burnished brass told the tales of India; of Sepoys and servants, Nawabs and Kings. A sweep of vast marble steps cascaded from the memorial’s entrance like a pure white waterfall. I climbed to the door and words failed me. To my Snapchat audience I said:

You walk inside this memorial to Queen Victoria and it just leaves you speechless. So I’m not even going to try to describe it. I’m just going to show you…

Later, outside in the garden, I stood beside a fountain, that was quintessentially Moghul ornament, and looked back at the Victoria Memorial, framed by arcing, crystal jets of water. Bright red flowers grew in colourful profusion around the fountain’s perimeter. Crows balanced on the green-painted railings. Women in bright saris promenaded along the nearby paths beneath groves of peepal and guava trees.

I tried to think of some glib closing line to say: something pithy and intellectual to close off my broadcasts from India. But I had nothing. The monument had left me speechless. I took out my phone and launched Snapchat for the final time in India and said:

Well…I don’t think that I can top that, so I’m not going to try.

Goodnight everybody.

The tumult and shouting dies;

The captains and the kings depart.

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dunes and headlands sinks the fire.

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday, is one with Nineveh and Tyre…

– Rudyard Kipling, Recessional.

THE END