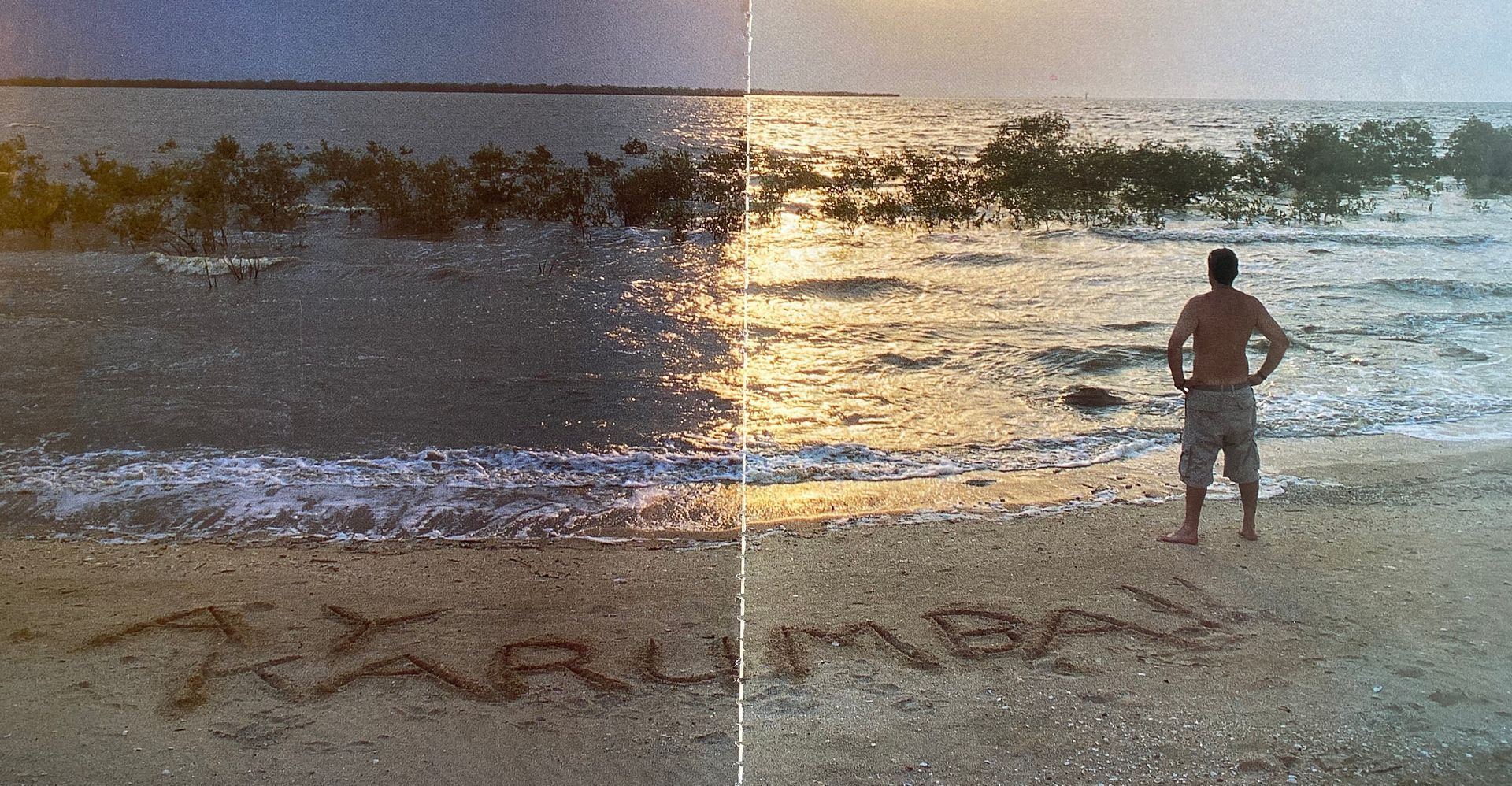

You’re in by Karumba,

Where the fishing boats come in;

I can’t believe this feeling,

But I wish that I was there,

Every passing day…

– Goanna, Every Passing Day

Fifteen nautical miles north-west of Karumba the oppressive air presses down on us with an almost tactile force. Thunderheads massed on the horizon foretell a cooling storm to come, but for now the four of us aboard the Kathryn M2 are at the mercy of the monsoonal heat. The boat’s hull cleaves the water of the Gulf of Carpentaria with a sibilant hiss; the diesel engine thrums beneath the deck plates. We are making eighteen knots, heading back to port with our day’s catch: three decent barracuda, a black kingfish and half a dozen Spanish mackerel. Standing on the bridge, with a cold beer in my hand, I watch the green smudge of the Australian coast drawing slowly nearer. Behind us, the boat’s wake unfolds across the sea which lies like a sheet of obsidian beneath the luminous immensity of the sky.

Karumba is situated in the south-east corner of the Gulf of Carpentaria: the southernmost extremity of the Arafura Sea. Nearby, where the sluggish Norman River falls into the Gulf, a delta of tidal creeks and wetlands extend inland in a series of meandering saltwater estuaries. This mangrove-choked landscape is the habitat of estuarine crocodiles (the bad ol’ boys of the crocodile world) and a vast array of bird species. The Gulf is located on the migratory path known as the East Asian Flyway and hundreds of thousands of birds use the region as a jumping-off point for their flights into Asia and beyond. Flocks of eastern bar-tailed godwits, fresh from their summer on the Avon-Heathcote Estuary, at Christchurch on the South Island of New Zealand, stop off to rest here en route back to their breeding grounds in Alaska.

The Port of Karumba was originally a refuelling and repair stop for the Empire Flying Boats, which connected Sydney to Great Britain. The aircraft landed on the stretch of the river in front of the town and during WW2 were the only aerial connection Australia had with the rest of the world. Karumba was also a Catalina Flying Boat base for the Royal Australian Air Force and the ramp onto which these amphibians taxied now forms one of the town’s streets.

I first heard of Karumba in the mid-eighties in a song called Every Passing Day by Australian band Goanna. At the time I was working on a High Country sheep station, deep in the heart of New Zealand’s Southern Alps. It was a world of sheep dogs and horses, hobnail boots and musterer’s huts, harsh winters and late snows. For me, Karumba was out on the edge of the world, about as far removed from the High Country as it was possible to get. Lying on my bed in the shepherd’s quarters, listening to that song while the nor’ west wind shrieked around the eaves, I imagined steaming mangrove swamps, crocodiles and tidal mud, fishing boats coming home in the sunset and endless, punishing heat. Karumba seemed like the sort of beyond the pale place I would never visit. And yet, in one of those strange twists that life can take, here I was, sailing home to Karumba after a day’s fishing on the Gulf, with the first flickers of lightning exploding across the sky and the air heavy with the scent of rain.

By the time we reach shore it is raining: a heavy, blattering downpour which pock-marks the opaque water of the river and runs in deluges from the scuppers. We adjourn to the Sunset Tavern (one of the few places in Eastern Australia where you can watch the sun set over the ocean) to relive the day’s escapades. Outside, sixty millimetres of rain falls in less than an hour. By nightfall the storm has moved on and a watery sliver of moon hangs in the sky.

Karumba is the southernmost port on the Arafura Sea: surely the most evocatively-named sea in the world. The name is redolent of pirates and pearling luggers, of spice islands and hidden mangrove coastlines. It’s the sort of sea that a character in a Joseph Conrad novel would set sail across: “blue and profound, without a stir, without a ripple, without a wrinkle, viscous, stagnant, dead.”

Prior to the European discovery of Australia, the Arafura Sea was the haunt of Macassan fleets from the Celebes Islands. The Macassans harvested beche-de-mer (a type of sea cucumber resembling a black, tumescent penis) which they cured on the beaches and sold to the Chinese as an aphrodisiac. Later, pearl divers came, then shrimp fisherman. Today, Karumba is home base for Australia’s largest shrimping fleet.

The day after my fishing trip is a Saturday. Nothing much is happening in Karumba. A few fishing boats come and go at the pier; the tide rises and falls among the mangroves and mooring ropes along the Norman River; mirages shimmer on the asphalt road leading out of town and into the Outback. Ceiling fans stir the tepid air in the Animal Bar of the Karumba Lodge Pub; next door, the Suave Bar is empty. I sit in the shade of a spreading fig tree outside the Post Office drinking chilled orange juice from a plastic bottle. Ants are nesting in a crack in the concrete sidewalk. A girl arrives in a dusty 4WD and empties the mail from box 71 of the 233 red mail boxes set into the wall. Magpie larks play in a listless, desultory fashion on the blue and orange phone boxes.

All day thunderheads have grumbled out on the plains. The sun is incandescent in the pewter dome of the sky. As afternoon wears on the heat grows more and more oppressive. Mosquitoes feed on my exposed skin and flocks of sulphur-crested cockatoos fly screeching from tree to tree. It is as if the natural world knows something is about to happen and is restive.

As the sun begins its descent into the sea, the horizon is shrouded by roiling clouds. Bolts of lightning jump earthward from the black belly of the storm. The atmosphere seems charged electricity and heavy with moisture. This is the real deal: the full spectacle of heat, convection, air masses, water vapour, static electricity and raw energy. The sun has gone out. All that remains is a pale, flat, eerie glow which casts no shadows. Huge knives of lightning slice the sky, thunder detonates overhead with ear-shattering force and the air turns the colour of soot. As the storm rages all around I take off my shirt and let the rain beat on my bare skin like a benediction.

Karumba is the sort of place which epitomises the adage “the journey is the destination”. You need to make a real effort to get there by driving west from Cairns through 800 kilometres of empty Outback. And, let’s face it, there’s not a lot to see once you’ve arrived. Sure, people come from all over the world for the excellent fishing. Campers spend months at the Sunset Point Caravan Park just doing nothing. And there is a zinc smelter to visit if you’re really stuck for entertainment.

But the real attraction of visiting a place like Karumba is being on the edge of the world. Tropical towns by the sea have a different feel to inland places. They look outwards, towards the emptiness of the ocean, away from the security and certainties of the land. For me the pleasure of being in Karumba lies in simply watching the sun set over the sea while the Sunset Tavern regulars, oblivious to the solar spectacle outside, gamble on television horses racing in other parts of Australia. It lies in the thrill of watching the violent arrival of a tropical storm after the ennui of a 45 degree day. And, best of all, it lies in the pure, unexpected delight of being in a place I have dreamed of for so long.

In Karumba I can smell the warm breath of Asia. Across the narrow waters of the Arafura Sea lie the jungle islands of Irian Jaya, the coral atolls of the Moluccas and the teeming shores of Indonesia. Yet even this close to Asia I am rooted firmly in white Australia. Satellite dishes beam the latest news of the world into town; every meal comes with chips and beetroot; men in grubby shorts and tee-shirts drink copious quantities of Victoria Bitter beer from ice-cold glasses; and, on the edge of town, Aboriginal people move like ghosts in their own land.

On my last evening in Karumba I drift down to the Sunset Tavern to watch my final Arafura sunset. Day ends suddenly in the tropics. Sunsets are always brief but spectacular. I sit on a rocky outcrop, still warm from the day’s heat, as the sun sinks inexorably into the sea and the sky turns the colour of spilled blood. Distant thunder clouds, piled on the horizon, are lit from within by strobes of lightning. As the sun disappears, the colour bleeds from the sky, the sea fades from pink to indigo, and night comes down like a theatrical curtain.

I sit for a while in the gloaming listening to the pulse of the ocean. The incoming tide roars on the shoreline with a noise like a distant cheering crowd. Karumba had once been a place which existed only as a collection of images conjured in my imagination by the words of a song. But now that I have seen it, Karumba is real. It has been burned into my memory during the time I have spent out here, under the sun on the edge of the world. The ocean glitters in the starlight and I know that, for the rest of my life, I will go to Karumba in my mind, once or twice every passing day.

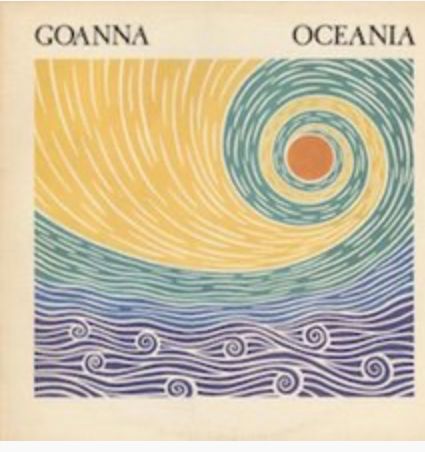

FOOTNOTE: Goanna’s 1984 album Oceania is a forgotten masterpiece. Upon its release it failed to chart and quickly disappeared from view. I bought a cassette copy of the album in 1985 from a record shop in Timaru on the South Island of New Zealand. I have it still: worn out, spliced and almost inaudible after thousands of playings. Oceania was never released on CD and, until August 2020, was unavailable in any form whatsoever. But in September 2020, after my daughter asked me what my all time favourite song is, I discovered that a remastered edition of the album had appeared on Spotify. I am listening to it now. It is my favourite album of all time and the song Every Passing Day , upon which this story is based, is my favourite song ever. The story itself, which appeared in the magazine Avenues in 2005, won a QANTAS Media Award for Best Magazine Travel Story in 2006. I’d like to return to Karumba some time soon, to smell the warm breath of Asia and watch the passing days out there on the edge of the world.