…the emu-sextons pay me a last cursory glance…

At Menzies, a dead-on-its-feet mining town a hundred kilometres north of Kalgoorlie, I turn off the bitumen highway onto a rutted track bulldozed through the red dirt landscape of Western Australia. My rented car moves about on the loose surface like a schooner under sail on a rough sea. A cloud of ochre dust from the wheels obscures the rearview.

After an hour or so, a signpost points down an even rougher track leading through scrubby sand hills to the edge of Lake Ballard. The empty lake, its bed white with salt crystals left behind when its ephemeral waters evaporated, lies pressed under the weight of the hot sky. Waves of heat distort the flat expanse of the lakebed, where fifty-one skeletal figures stand immobile in the shimmering air. I leave the car parked in the sparse shade of a bloodwood tree and begin to walk.

The Inside Australia installation is a collection of metal sculptures set up on Lake Ballard in 2003 by English artist Antony Gormley. The sculptures are based on computer scans of the inhabitants of Menzies, rendered in alloys of iron, molybdenum, iridium, vanadium and titanium. According to his website, Gormley sought “to find the human equivalent for this geological place.”

“I think human memory is part of place,” he wrote, “and place is a dimension of human memory.”

Out on the lake bed, I am alone in my own dimension of heat, flies and sweat. The red mud of the lake floor, overlaid with its rime of salt, has dried and cracked like the skin of a reptile. It’s slightly sticky surface sucks at my jandals, which, in hindsight, were not the best choice of footwear for exploring the widely-spaced components of Inside Australia.

Each of Gormley’s works is set a distance of seven hundred and fifty metres from its neighbour. The footprints of previous visitors trace indistinct pathways leading from sculpture to sculpture in a long loop around the lake. From a distance, the sculptures are merely vague outlines: shadows caught in the distorted, iridescent air. Up close, they are eerie, with outstretched arms, protruding breasts and shrunken heads.

The midday sun casts foreshortened silhouettes of each statue onto the ground, simplifying their forms even further, like the charcoal rock drawings of Aboriginals. As the sun moves across the sky, the shadows change shape and size, each one describing a sun-dial ellipse around the sculpture’s feet.

It takes two hours for me to complete my circuit of the sculptures. Back at my the car, my sweat- and dirt-stained reflection in the windscreen looks vaguely like a component of Inside Australia , seared by heat and light. I start the engine and let the air-con revive me before returning to the road.

As afternoon cools into evening, I walk alone through a deserted desert town. Whereas at Lake Ballard I had seen human shapes inhabiting an empty landscape, here in the abandoned mining town of Gwalia I walk through an urban space devoid of human forms.

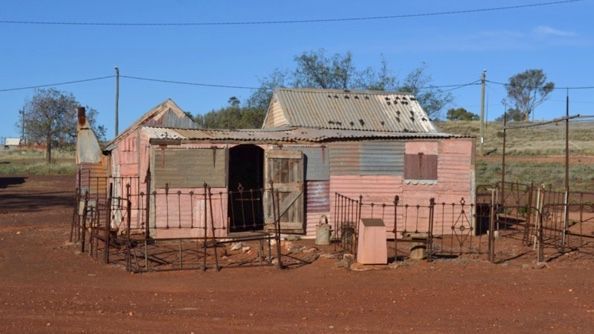

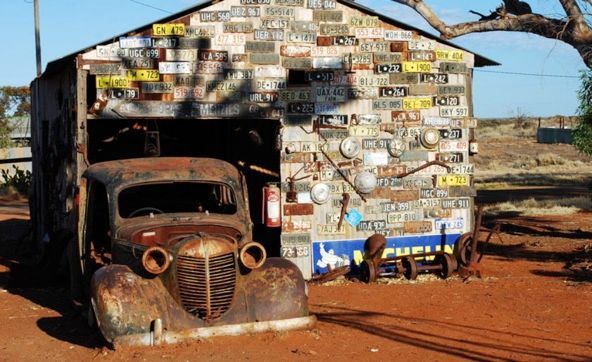

The timber and tin buildings stand sway-backed and forlorn beneath the empty sky. Front doors hang agape in their frames, giving views down the throats of hallways to the rooms inside. Windows stare sightlessly out across the dusty street. A pair of morose emus, like feathered sextons in a kindling cemetery, watch me in a desultory fashion as I wander the ruins.

From 1897 until 1963, the Sons of Gwalia Gold Mine was the life-blood of Gwalia. The rough-and-ready township grew up around the nearby mine-shaft, which descended for a kilometre into the hard granite beneath the town. By 1910, more than a thousand people called Gwalia home. During its lifetime, the mine yielded 2.6 million ounces of gold: worth about NZ$2.4 billion at today’s prices.

But in the early sixties, the gold ran out. In December 1963, the owners closed the mine. Trains were dispatched to convey the remaining miners, their families and whatever they could carry to Kalgoorlie. Overnight, Gwalia became a ghost town.

The setting sun casts long shadows between the buildings. Inside the kitchen of a once-comfortable miner’s cottage, tiny shafts of light pierce the gloom through bullet-hole gaps in the tin walls. Cast iron pots stand on the long-cold stove; a table set with two plates and a fork sits askance on the disintegrating floorboards. Faded newspapers cover the walls in lieu of wallpaper.

Inside another cottage, books that will never again tell their stories stand on a shelf above a bed which will never feel the weight of a sleeping body. The roof is open to the sky. A glassless lantern, which will never light another night, hangs beside a back door opening onto the endless space of the Outback.

The grimy windows of Mazza’s Store – “Birthday Goods, Tobacco and Lino” – reflect the last rays of the setting sun as I sit on the store’s verandah watching the day end in Gwalia. Funereal crows, whose gurgling cries are the ghost voices of the Australian bush, perch in a nearby scribbly gum.

I imagine Gormley’s iron sculptures, radiating the day’s heat back into the air over Lake Ballard. Here in Gwalia, it is the past which radiates: in the deserted homes of the people who once gave this place a dimension of human memory. Their day’s work done, the emu-sextons pay me a last cursory glance before ambling off towards the abandoned pub.