Out where the river broke,

The bloodwood and the desert oak..

– Midnight Oil, Beds Are Burning

At Roper Bar I was swimming with crocodiles. And not the harmless freshwater variety, either. These were the real deal: big ‘ol, bad-tempered, drag-you-under-and-drown-you saltwater crocs. The sort of creatures only Crocodile Dundee could handle.

I had joined pilot Paul Smith and his friend Brigit, both of whom worked at the nearby Ngukurr Aboriginal Community, for a swim where the Roper River tumbles over a rocky slab of granite which gave the area its name. As we lolled in the cool water, Paul’s eyes constantly scanned the river for the tell-tale ripple of an approaching croc.

“We’re fine swimming here in the shallows as long as someone watches the river,” Paul said. “But out here you should never swim alone or even go near the water unless someone has told you it’s safe.” Of course where crocs are concerned, “safe” is a dangerously loose term. So when the setting sun began casting shadows on the river, making it harder to see into the water, I was happy to return to the campground and leave the Roper in the care of its Silurian masters.

Dawn in the Australian Outback is always heralded by the strangled gurglings, maniacal cackling, rasping, clicking and guffawing of birds. As I lay awake in the pre-dawn darkness, a pied butcherbird sang limpid notes in the tree above my tent, like a bell tolled in liquid. I rose at 5.30am, lit my petrol stove and ate peaches out of a can while the water boiled. One of the simplest pleasures of travelling in the bush is waiting for the billy to boil for a dawn cuppa. A pair of whistling kites eyed me from a tree-top as I broke camp.

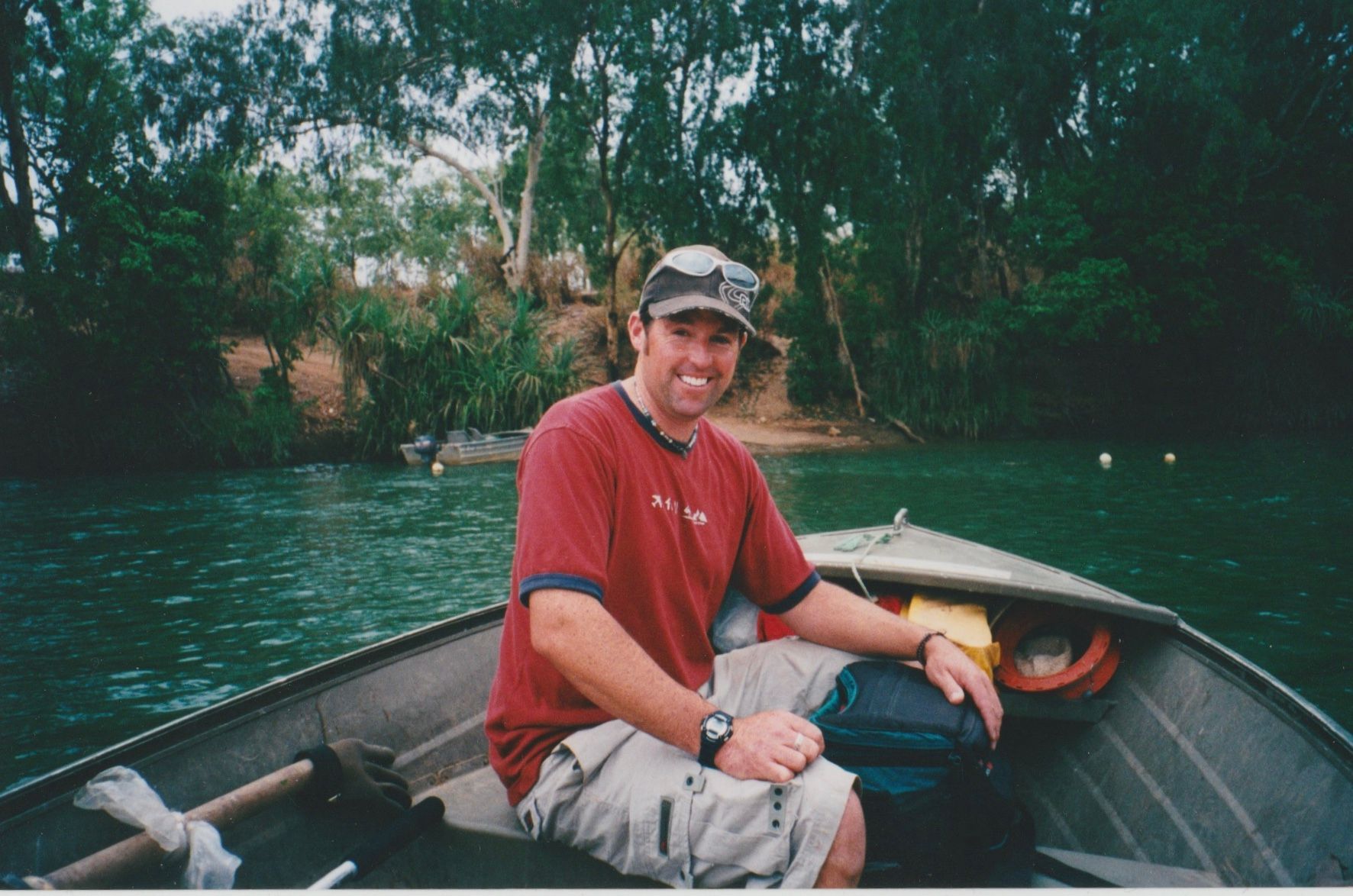

Beyond Roper Bar the road became absurdly rough: corrugations, bull-dust and potholes you could lose an oil drum in. After an hour or so I stopped at the Tomato Island fishing camp. Mick and Rita Caulfield were mooring their aluminium dinghy beside a concrete boat ramp leading down to the glassy Roper River. Mick held a big barramundi Rita had caught. They invited me to visit their nearby camp.

Mick, stocky and graying, was a motorbike mechanic; Rita was a nurse who worked part-time at the Ngukurr Community, a five-minute boat-ride across the river. We drank coffee and they told me how they had quit their busy lives in Melbourne for the solitude of the Northern Territory bush.

“We went away for twelve months,” Rita said. “That was two years ago and we’re not ready to stop yet.”

“We spent the Wet (the rainy season) in Darwin last year,” Mick added. “Might settle down there when the time comes.”

Later, Mick took me upriver in the dinghy to see the wreck of the Young Australian. The bush grew down to the water’s edge; the river hid its secrets (and its terrors) beneath the glossy, opaque surface.

The wreckage of the boat, run aground at night by a drunken crew in 1873, lay against the upstream edge of a rocky islet. The rusted boiler, with its fire-door agape, had the appearance of a half-submerged skull. I imagined the horror of a sinking boat, the men scrambling blindly in the darkness as the water swirled across the deck-plates, and a crocodile-infested river to swim to safety.

Beyond Tomato Island camp the road hugged the right bank of the river. The radio picked up a broadcast in Pidgin English from Ngukurr. I sat for a while beside a lily-covered lagoon and listened to thunder growl in the distance. But it was an empty threat and no rain came.

Later, I hiked alone through the Southern Lost City, where eons of erosion have sculpted the hard granite into a natural architecture of towers, abutments, arches and grottoes. The hot wind had desiccated the surrounding bush and everything felt tinder-dry and lifeless.

I reached the dusty, red-sand township of Borroloola in the late afternoon. I had a cold drink at the local store, called home on the satellite phone, then drove out to King Ash Bay fishing camp, situated where the McArthur River drains languidly into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

I pitched my tent overlooking the river then retired to the Groper Bar for a beer. The bar occupied a rough corrugated shed with a big circular awning out back. Beers were served straight out of a rusty chest freezer. There were eleven other drinkers at the bar, mostly retired-looking gents in grubby singlets and shorts. A wall-eyed dog sprawled in the dirt.

The kitchen sold a range of fried food (is there any other kind at a fishing camp?) and as I worked my way through a giant steak one of the locals came over.

“That your tent by the river, mate?” he asked. I nodded and he continued. “If I was you I’d shift it back from the water a bit.”

I thought back to the Roper Bar and how I’d survived actually sitting in a river full of crocs. Surely I would be safe thirty metres from the river. Mick Dundee wouldn’t have been worried. Sensing my reluctance the old-timer glanced down at the hunk of red meat on my plate then back up at me.

“We’d hate to see you end up like that, mate,” he grinned. ”S’up to you but anything would be better than being eaten by a bloody croc.”